THE NEWS REACHES MANCHESTER

|

|

On the afternoon of the crash Alf Clarke had telephoned the Evening Chronicle sports desk to say that he thought the flight would be held up by the weather and made arrangements to return the following day. By three in the afternoon the paper had more or less `gone to bed', and the final editions were leaving Withy Grove. In other parts of the city the daily newspaper staffs were beginning their routines. Reporters were heading out on diary jobs; sub-editors were looking through agency stories to see what was to form the backbone of the Friday morning editions.

That weekend United were to play League leaders Wolves at Old Trafford. Despite the long journey home it looked on form as if the Reds would close the four-point gap at the top of the table, putting them just one victory behind Billy Wright's side, and ready to increase their efforts for that third successive Championship. Could United emulate Huddersfield Town and Arsenal? Surely if they did it would be an even greater achievement than in those pre-war days. Saturday was coming round again. United would make the headlines. Then on the teleprinter came an unbelievable message: `Manchester United aircraft crashed on take off..... heavy loss of life feared.' The BBC interrupted its afternoon programming to broadcast a news flash. The football world listened to the words but few understood their meaning.

Jimmy Murphy, Matt Busby's wartime friend and now his assistant, was manager of the Welsh national side, and a World Cup qualifying game had coincided with the Red Star fixture. Murphy told Matt Busby that he would go to Yugoslavia rather than the game at Ninian Park, Cardiff, but his manager told him that his place was with the Welsh side.

"I always sat next to Matt on our European trips," Murphy recalls, "but I did what he said and let him go off to Red Star without me. Mind you, I've got to be honest - my mind was more on our game in Yugoslavia than the match I was watching. When I heard that we were through to the semi-final it was a great load off my mind; I didn't like not being there."

He had just returned to Old Trafford from Wales when news of the air crash reached him. Alma George, Matt Busby's secretary, told him that the charter flight had crashed. Murphy failed to react.

"She told me again. It still didn't sink in, then she started to cry. She said many people had been killed, she didn't know how many, but the players had died, some of the players. I couldn't believe it. The words seemed to ring in my head. Alma left me and I went into my office. My head was in a state of confusion and I started to cry."

The following day Jimmy Murphy flew out to Munich and was stunned by what he saw:

|

|

"Matt was in an oxygen tent and he told me to `keep the flag flying'. Duncan recognised me and spoke. It was a terrible, terrible time."

Murphy was given the job of rebuilding. Life would go on despite the tragedy, and Manchester United would play again:

"I had no players, but I had a job to do."

After the agency newsflash had reached the Manchester evening newspapers, extra editions were published. At first details were printed in the Stop Press. By 6 pm a special edition of the Manchester Evening Chronicle was on sale:

"About 28 people, including members of the Manchester United football team, club officials, and journalists are feared to have been killed when a BEA Elizabethan airliner crashed soon after take-off in a snowstorm at Munich airport this afternoon. It is understood there may be about 16 survivors. Four of them are crew members".

The newspaper, which was carrying Alf Clarke's match report and comments from the previous night's game, said on its front page: `Alf Clarke was talking to the Evening Chronicle reporters in Manchester just after 2.30 pm when he said it was unlikely that the plane would be able to take off today.' Even though only three hours had elapsed since the crash the newspaper had a detailed report of how the disaster occurred.

Twenty-four hours later, as the whole of Europe reacted to the news of the tragedy, the Evening Chronicle listed the 21 dead on its front page under a headline: `Matt fights for life: a 50-50 chance now'. There was a picture of Harry Gregg and Bill Foulkes at the bedside of Ken Morgans, and details of how the other injured were responding to treatment. The clouds of confusion had lifted - Munich had claimed 21 lives, 15 were injured and, of these, four players and Matt Busby were in a serious condition.

Workmen pay their respects as a cortege leaves Old Trafford.

Supporters kept vigil at the stadium as the football world

mourned the passing of the Babes.

Workmen pay their respects as a cortege leaves Old Trafford.

Supporters kept vigil at the stadium as the football world

mourned the passing of the Babes.

|

In the days following, Manchester mourned as the bodies of its famous footballing heroes were flown home to lie overnight in the gymnasium under the main grandstand before being passed on to relatives for the funerals. Today that gymnasium is the place where the players' lounge has been built, where those who succeeded the Babes gather after a game for a chat and a drink with the opposition.

Thousands of supporters turned out to pay their last respects. Where families requested that funerals should be private, the United followers stayed away from gravesides but lined the route to look on in tearful silence as corteges passed.

Cinema newsreels carried reports from

Munich, and the game itself responded with memorial services, and

silent grounds where supporters of every club stood, heads bowed, as

referees indicated a period of silence by a blast on their whistles.

Desmond Hackett wrote a moving epitaph to Henry Rose, whose funeral was

the biggest of all. A thousand taxi drivers offered their services free

to anyone who was going to the funeral and there was a six-mile queue

to Manchester's Southern Cemetery. The cortege halted for a moment

outside the Daily Express offices in Great Ancoats Street where Hackett

wrote in the style of Henry:

`Even the skies wept for Henry Rose today.....'

FOOTBALL RETURNS TO OLD TRAFFORD

Rival clubs offered helping hands to United. Liverpool and Nottingham Forest were first to respond by asking if they could do anything to assist. Football had suffered a terrible blow. To give United a chance of surviving in football the FA waived its rule which `cup-ties' a player once he has played in an FA Cup round in any particular season. The rule prevents him from playing for another club in the same competition, so that if he is transferred he is sidelined until the following season. United's need for players was desperate and the change of rules allowed Jimmy Murphy to begin his rebuilding by signing Ernie Taylor from Blackpool.

Manchester United took a deep breath. Football would return to Old Trafford. Thirteen nights after news of Munich had reached Jimmy Murphy the days of torture ended when United played again. Their postponed FA Cup-tie against Sheffield Wednesday drew a crowd of 60,000 on a cold February evening of immense emotion. Spectators wept openly, many wore red-and-white scarves draped in black - red, white and black were eventually to become United's recognised colours - and the match programme added a poignant final stroke to a tragic canvas.

Under the heading `Manchester United' there was a blank teamsheet. Spectators were told to write in the names of the players. Few did, they simply listened in silence as the loudspeaker announcer read out the United team. Harry Gregg in goal and Bill Foulkes at right back had returned after the traumas of Munich, other names were not so familiar.

At left fullback was Ian Greaves who had played his football with United's junior sides and found himself replacing Roger Byrne:

"I can remember the dressing room was very quiet. I couldn't get Roger out of my mind; I was getting changed where he would have sat. I was wearing his shirt..."

At right-half was Freddie Goodwin, who had come through from the reserve side after joining United as a 20-year-old. He had played his first League games in the 1954-55 season. Another reserve regular was centre-half Ronnie Cope, who had come from United's juniors after joining the club in 1951. At left half was Stan Crowther, whose transfer to United was remarkable. He played for Aston Villa, and was not very keen to leave the Midlands club. Jimmy Murphy recalls:

"Eric Houghton was Villa manager at the time and he had told Stan that we were interested in him. He didn't want to leave Villa, but Eric got him to come to Old Trafford to watch the Sheffield Wednesday game. On the way up he told him he thought that he should help us out, but Stan told him he hadn't brought any kit with him. `Don't worry, I've got your boots in my bag,' Eric said. We met at about half-past five and an hour before the kick-off he'd signed!"

Colin Webster at outside right had joined United in 1952 and made his League debut in the 1953-54 season. He had won a League Championship medal in 1956 after 15 appearances, but had since been edged out of the side by Johnny Berry. Ernie Taylor was inside right, and at centre forward was Alex Dawson, a brawny Scot who had made his debut as a 16-year-old in April 1957, scoring against Burnley. Inside-left was Mark Pearson, who earned the nickname `Pancho' because of the Mexican appearance his sideburns gave him. Like the Pearson who preceded him, Stan, and the one who was to follow him almost two decades later, Stuart, Mark was a powerful player and a regular goal scorer with the lower sides. That night he took the first steps of his senior career. The new United outside-left was Shay Brennan, who was a reserve defender. Such was United's plight that the 20-year-old was to begin his League career not as a right back but as a left-winger.

Sheffield Wednesday had no chance. Murphy's Manchester United were playing for the memory of their friends who had died less than a fortnight earlier. The passion of the crowd urged them on. To say that some played beyond their capabilities would be unfair, but with Wednesday perhaps more affected by the occasion than the young and new players, the final score was United 3 Wednesday 0.

Playing in the Sheffield side was Albert Quixall, later to join United in a record transfer deal, who recalls:

"I don't think anyone who played in the game or who watched it will ever forget that night. United ran their hearts out, and no matter how well we had played they would have beaten us. They were playing like men inspired. We were playing more than just eleven players, we were playing 60,000 fans as well".

United scored in the 27th minute after two errors by Brian Ryalls in the Wednesday goal. Bill Foulkes had taken a free kick from well outside the penalty area and his shot was going wide when Ryalls palmed it away for a corner. There had seemed no danger from the shot, but Brennan's corner kick brought his first goal for the senior side. Ryalls tried to collect the cross under the bar and could only turn the ball into his own net.

Brennan got a second later in the game when a shot from Mark Pearson rebounded off the 'keeper and straight into the Irishman's path. He made no mistake and United led 2-0. Five minutes from the end of that unforgettable night Alex Dawson scored the third. United had reached the quarterfinals of the FA Cup. The crowd turned for home, their heads full of memories of that remarkable game, their hearts full of sadness as they realised the full extent of Munich. The new team had carried on where the Babes had left off.... but they would never see their heroes again.

Two days after that cup-tie Duncan Edwards lost his fight to survive, and the sadness of Munich was rekindled.

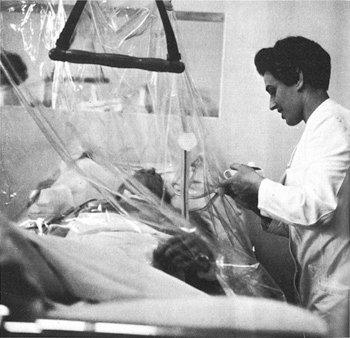

Matt Busby lies in the oxygen tent as he fights for his life in

the Rechts der Isar Hospital.

Matt Busby lies in the oxygen tent as he fights for his life in

the Rechts der Isar Hospital.